Complexion Changes in Victorian Literature

Introduction

Throughout the Victorian period, dominant discourses changed as technology and science progressed. Literature adapted to this change by implementing the current ideologies into their narratives. The discourses not only related to the readers of the time, but also shaped how certain actions and ideas were conveyed in the book. A reader’s interpretation may vary with the discourse they believe in. Over time, society’s main ideas about policing someone and upholding societal standards changed; many things that once meant one thing now meant another. Analysis of certain genres of fiction, specifically how they handle the shift in dominant discourse, can lead to the recognition of how vocabulary changes along with the genres. The dominant discourses present in sentimental and sensational fiction reflect contextual changes in complexion-related vocabulary by shifting its focus from physiological, direct causes of complexion changes, to psychological, indirect causes of complexion changes.

To examine this idea, I will use a combination of primary sources and secondary sources to explain what dominant discourses were at the time of the publication of two sentimental novels and two sensational novels. I will utilize technology to aid in my data collection and visual representation of that data. From the data I collect, I will then draw conclusions on what the context surrounding the words imply and describe the relationships I find between words and dominant discourses.

Historical Context: Sentimental Fiction

Sentimental fiction was the most popular and most embraced form of fiction during the 1850s. Although there is no concrete, specific definition for this genre of fiction, the ideas society had during its popularity gave the genre something to follow and reflect. Because of this, dominant discourses shaped sentimental fiction to be a socially acceptable and extremely well received genre. Therefore, dominant discourses must be analyzed to reveal the traits of sentimental fiction. One dominant discourse of the period was the belief that society was a social body. Author Mary Poovey expands on this idea in her book Making a Social Body:

By 1776, the phrase body politic had begun to compete with another metaphor, the great body of the people. As Adam Smith used this phrase in the Wealth of Nations, it referred not to the well-to-do but to the mass of the laboring poor. By the early nineteenth century, both of these phrases were joined by the image of the social body, which was used in two quite different ways: it referred either to the poor in isolation from the rest of the population or to British (or English) society as an organic whole. The ambiguity that this double usage produced was crucial to the process of cultural formation I am describing, for it allowed social analysists to treat one segment of the population as a special problem at the same time that they could gesture toward the mutual interests that (theoretically) united all parts of the social whole. The phrase social body therefore promised full membership in a whole (and held out the image of that whole) to a part identified as needing both discipline and care. (Making a Social Body Poovey 7-8)

Thus, British society during the late 1700s and into the late 1800s viewed itself as an autonomous body. The body, made up of all the social classes, had to watch the other classes to make sure that everyone was in check. In other words, people were expected to behave the way their classes behaved and regulate those that were not acting appropriately.

Although all social classes were expected to behave the right way and confined to those behaviors, women were even more restricted. Another book by Mary Poovey called The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer expands on that concept. She details the legal reasons as well as social reasons women were controlled by social institutions like religion, property, and morality:

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the legal status of women remained as it had been defined under Roman law. The law of “coverture” decreed that “the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection and cover, she performs everything.” (The Proper Lady Poovey 7)

In addition to being under the husband’s identity, religion defined a space where women should be. More specifically, Puritan doctrines were pushed and emphasized to keep women in the domestic sphere. For example, Poovey writes that the Puritans “promote their goal of spiritual and social reformation by emphasizing the importance of the family as a unit of religious and social discipline” (7). The focus on the family structure in the doctrines “tended, in practice, to restrict women’s activity to narrowly defined domestic duties” (7). Thus, women were always taught to be a part of the household and to never break the patriarchal family structure.

Another main role for women was to encourage their husbands. Due to the growth of the middle classes, society encouraged women to fulfill that duty. Poovey explains that the development of the middle classes “enhanced women’s position and gave female nature a more strict—if idealized—definition. The duties a woman fulfilled in the home directly supported capitalist values” (10). Essentially, it was the woman’s job to maintain the house and the children. Once their husband came home from work, they would reward him and refresh him so he could come back to work the next day more energized. At the same time, women also had to teach her children “a morality centered on discipline and self-control; in doing so, she helped promote the values necessary to another generation of successful competitors” (10). Thus, the woman’s responsibility was to care for her husband, children, and house all while maintaining her morals, virtues, and remain in the domestic sphere.

Next, emotional representations of characters were important in sentimental fiction. During this period, a “cult of sensibility” movement was pushed onto society. In the simplest terms, “cult of sensibility” can be defined as a movement that “celebrated a response to life charged with high emotion” (Oxford Reference). Essentially, the cult of sensibility emphasized high emotional representation in literature and other art forms. It romanticized emotional responses. To follow societal ideas, sentimental fiction emphasized emotions, the place of women in society and the domestic sphere, marriage plots, and keeping the public sphere and domestic sphere separated.

Reading complexions in sentimental novels focused on character’s reactions to external stimuli and as reactions to fear. For example, when a character was sick or fatigued, they turned pale. Additionally, if someone told the character something that may scare them, or if the character witnessed something that shocked them, they turned pale. In this genre, changes in a face’s color are reactions external stimuli and are simply descriptive details to add more life to the character. Not only that, the cult of sensibility mindset emphasized reactions to emotions which is significant with a character’s reaction to fear or embarrassment.

The two sentimental texts chosen for this project are The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Bronte and Villette by Charlotte Bronte. These were both published toward the end of the sentimental era of fiction but still left a significant mark on Victorian literature. When compared to each other, their plots are different, but both focus on virtues, morals, and the importance of privacy regarding the domestic sphere. They adhere to the dominant discourses of the period through character behaviors, descriptions, and plot structure.

The first selection, Anne Bronte's sentimental novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, tells the story of a young farmer, Gilbert Markham, and his fascination with a widow and her son that just moved into the long vacant Wildfell Hall. He recalls the events in the form of a long letter to his friend Jack Halford. Gilbert falls in love with the widow, Helen Graham, despite not knowing much about her or her son, Arthur. She also feels something for Gilbert, but she is hesitant to act on that feeling. To give her a glimpse into her complicated past, Helen ends up giving him her diary. Her diary entries make up the inner narrative of the novel, framed by Gilbert’s narrative. Helen's past is revealed to the reader as well as her strength and independence. She used to be married to a rich drunkard named Arthur Huntingdon, but she took her son and fled after Huntingdon’s cruel mistreatment of them.

Now knowing why Helen is so secretive and cautious, Gilbert falls even more in love with her even though she is hesitant to be in a relationship again. Feelings come to a head when Helen leaves suddenly to care for her dying husband. A misunderstanding leads Gilbert to believe that Helen is interested in someone else which leads to a hasty pursuit. In the end, the misunderstanding is resolved, and Gilbert and Helen marry. This novel tackles heavy issues such as alcoholism, domestic violence, and female agency, but resolves with a happy ending for Gilbert and Helen.

The other sentimental novel Villette centers around a lonely yet independent woman named Lucy Snowe. Without much family or purpose, the young woman boards a ship from England to the continent to look for a new opportunity at life. On the way there, she hears about a boarding school in the French town of Villette. She takes a chance and travels to that school to look for a job as an English teacher, despite not knowing much French. Madame Beck, the headmistress of the boarding school, gives Lucy the job. The narrative follows Lucy's experience at the boarding school and her feelings about students, teachers, her godfamily that she used to live with, and her fluctuating mental state.

Toward the end of the novel, she learns that fellow English professor Paul Emmanuel has feelings toward her. Even though they both butt heads, he helps Lucy gain some confidence in herself. He also gifts Lucy her own place to start a school. Although she has always been an independent person, the gifts from Emmanuel as well as the better relationship with her godmother and son, her independence is more comforting, and she does not feel nearly as isolated as she once did. It ends with Lucy finally feeling content with herself and her life.

Historical Context: Sensational Fiction

In 1994, Lyn Pykett published a short book called The Sensation Novel from The Woman in White to The Moonstone that focused on sensation fiction which included its origins, its traits, and how authors fit into that genre with their works. The definition of sensation fiction is long and complex, but Pykett breaks it down into a more digestible format:

These electrifying novels of ‘our own days’ were mainly distinguished by their devious, dangerous, and in some cases, deranged heroes and (more especially) heroines, and their complicated plots of horror, mystery, suspense, and secrecy. The sensation plot usually consisted of varying proportions and combinations of duplicity, deception, disguise, the persecution and/or seduction of a young woman, intrigue, jealousy, and adultery. The sensation novel drew on a range of crimes, from illegal incarceration (usually of a young woman), fraud, forgery (often of a will), blackmail and bigamy, to murder or attempted murder. (Pykett 4)

Additionally, although other fiction during this time did have some elements of mystery, sensational fiction emphasized it. Due to its intense subject matter at the time, this genre was hit or miss for many people because it was a subversive discourse.

The reason sensation fiction took off was due in part to the dominant discourses at the time. Pykett states that the 1860s “was the age of “sensational” advertisements, products, journals, crimes, and scandals…the age of sensational theatre…” (1-2). Different forms of media were starting to take a dramatic turn. Unlike sentimental fiction and its corresponding societal ideas, sensational fiction acted as the contrary form. Even though it played on dominant discourses, like how sensational media did so well in society, it was subversive in fiction. It disrupted the public and domestic sphere and did what sentimental perspectives avoided—it exposed private matters. While the middle class enjoyed sensational stories, the upper class frowned upon the narratives, especially because many of the crimes or mystery taking place in the narratives happened with upper class characters which resulted in shattered reputations and ideas of corruption. Because of the upper class’s distaste for the genre and the middle class’s fascination of it, the differing opinions resulted in sensational fiction being subversive to sentimental fiction. Journalism during this time also reflected this by bringing the “world of the common streets, and the violent or subversive deeds of criminals were carried across the domestic threshold to violate the sanctuary of home” (2). Thus, the public sphere became more concerned with the domestic sphere. The importance of the privacy of domestic spheres was lessened.

Contrary to sentimental novels, reading complexions in sensational novels was more oriented around finding out someone’s true inner character. While sentimental novels embraced complexion changes caused by external stimuli such as sickness or environmental factors, complexion changes happen more in sensational novels because of internal stimuli or feelings. In this genre, changes in a face’s color are reactions to internal realization. The obsession with internal character, especially regarding how innocent someone is, took center stage in this genre. In addition, because the genre’s main narrative convention was mystery, complexion changes were subtle details to hint at a character’s true intentions.

The two novels out of my selection that are considered sensational texts are The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins and Lady Audley’s Secret by Mary Elizabeth Braddon. Both novels started as serialized stories and later were published as full novels. Collins’s story is written through several perspectives to form a court case. Braddon’s story is not written in the same form, but it is told through third person point of view and focuses mainly on the protagonist, a lawyer and pseudo-detective trying to find out what happened to his missing friend.

In 1859 after starting as a serialized story appearing every week in a newspaper, The Woman in White was published as a book. This story is regarded as one of the most well-known sensational novels ever published. The narrative is told through several perspectives that act like court documents or witness statements. Walter Hartright, a drawing teacher, begins the story recalling a strange encounter with a woman in white that appears to be running from somewhere. Later he receives a job to be the private drawing teacher to two wealthy young women, Marian Halcombe and Laura Fairlie.

Walter falls in love with Laura only to have his hopes crushed as she is arranged to marry Sir Percival Glyde, a baronet. The woman in white, Anne Catherick, who looks a lot like Laura Fairlie-Glyde, shows up throughout the narrative to warn Laura and Marian of Sir Percival and his friend Count Fosco. Through many twists and turns, it is revealed that Sir Percival is not who he says he is and at one point was in a relationship with Anne before he locked her away in an asylum. In the end, Walter helps Laura break away from the marriage and resolves the legal issues surrounding it. Walter finally can marry Laura and Marian lives alongside them.

The other novel in this study, Lady Audley’s Secret, started out as a serialized story appearing in English newspapers either weekly or biweekly, was published in 1862. The narrative opens with a beautiful woman named Lucy Graham marrying wealthy Sir Michael Audley. Not much is known about Lucy as she was just a normal governess to a local doctor. The next chapter introduces George Talboys, a young man returning from Australia with riches he received from mining. He hopes to please his wife with the money as they are not financially stable. He meets up with his friend Robert Audley, Michael Audley's nephew, when the ship arrives on land and that's where George sees that his wife, Helen, died before George came home. Robert attempts to help George with his grief, but later George disappears.

The narrative unfolds into a murder mystery and all suspicious signs point to Lucy Graham. Concerned about George's whereabouts, Robert leads an investigation into Lucy, who acts suspicious around him. After going around to several cities and talking with several of Lucy's old friends, he finds that Lucy is George's "dead" wife. She admits that she pushed George down a well. She does not know he survived and neither does Robert until after he sends Lucy to an asylum. Other subplots unfold along with the main story, but ultimately Michael ends his relationship with Lucy and George continues to heal alongside his best friend, Robert.

Reasons for Complexion Changes

Complexion changes in sentimental fiction had two primary uses. Firstly, complexion changes resulted from certain environmental stimuli whether that be alcohol, sickness, or fatigue—a physiological reaction. Mary Ann O’Farrell, author of Telling Complexions: The Nineteenth-Century English Novel and the Blush, describes another reason that result in color changes:

By means of its attentions to blushing as a perceived event of the body, the novel suggests that—in seeming involuntarily and reliably to betray a deep self—blushing assists at the conversion of legibility into a sense of identity and centrality. The novel values this sense of identity, even or especially when it is produced by the pains as well as the pleasures of mortified self-recognition and self-revelation; the painful blush lends the credible support of the body to the self that is generated, recognized ,and revealed in all the felt of ostensible uniqueness of its discomfiting mortifications. Construed in this way, the blush—as an act of self-expression—performs a somatic act of confession. (O’Farrell 5)

Although the focus of this study is not on the act of blushing, the ideas O’Farrell describes can be applied to paling. Since paling is also a complexion change caused from either external or internal stimuli, it can also be perceived as an “act of self-expression.” She also touches on the blush as a reaction to personal mortification. This reaction was common in older sentimental fiction and is often associated with the stereotype of proper ladies blushing during inappropriate conversations or personal matters. Paling can also be the result of such mortification, especially if the internal stimuli of realization results in the character feeling mortified. Additionally, experiencing a scare or embarrassment leads to paling. Mentioning the color of complexions was a common descriptive pattern in the genre of sentimental fiction and despite blushing complexions being more common, paling complexions could be applied to the same situations or internal epiphanies a character experienced.

As for sensational fiction, complexion changes are used in mostly the same way. It also utilizes physiological changes caused by environmental factors. Additionally, it does have a reaction to internal ideas but instead of mortification, it is more evidence of a confession:

Foucault’s notion of the power’s productivity (as opposed simply to its prohibitions) has been useful for this study, which develops the notion that, as a productive response to circumstance, blushing is precisely a social obligation felt as an urge, an act of somatic confession that dazzles with its promise to establish unique identity by revealing the body’s truth. (5-6)

Sensational fiction heavily emphasizes the internal confession of a character. In other words, this genre of fiction utilized complexion changes as the vessel to which another character, or the reader, may think that the blushing or paling character is guilty of something. Complexion changes confessed a character’s true feelings even if the character would never admit to them. With the rise of mystery and crime plots in sensational narratives, paling complexions revealed the true feelings of a character and subliminally hinted at their guilt, implying an internal confession.

Methodology

Although it is possible to study other vocabulary in these novels, I am focusing solely on complexion-related terms. Victorian literature includes changes of complexion and body language frequently throughout its narratives. In both genres, behavior is scrutinized because society enforces that kind of policing. Each of the four novels I have chosen include a plethora of instances regarding changes in complexion. The significance of these words stems from the context surrounding them.

I used an online program to pinpoint and count the words I was looking for. Voyant Tools is a website where users can upload a PDF or URL. The uploaded document is scanned by the website. The scan counts the number of times all words are used as well as graph the word’s frequency. It also allows the user to look up a specific word and get a glimpse of the context surrounding it, or the collocations of that word. Instead of manually searching a novel for the words, this program allowed me to quickly find and study the words and its collocations.

I took free PDFs of each novel and pasted it onto a Word document so I could clean it up. I deleted any copyright info or unnecessary title pages so I could have as accurate data as possible. Then I pasted the clean text into Voyant Tools. I recorded how many times the term appeared over the narrative. I also copied the graphs that visualized where the terms were over the course of the text. Next, I looked at collocations of the word. Collocations are what words appear around the term, or the context surrounding the term. Analyzing the collocations gave me a better understanding of how complexion terms were used in each text.

At the beginning of this project, I searched over two dozen terms. Most of the terms were variations of words, or lemma (for example, I searched “red,” then searched “redness,” “reddened”, “reddens” and other terms). I created an Excel spreadsheet and created five columns, a column for the term and the other four columns for each novel I read. Then, I recorded the frequency of the terms used. Once all the data was gathered on one table (see Appendix A), I then narrowed it down to the six most common words (see Appendix B). I took screenshots of the graphs related to each term for each text to study the visual of where terms appeared most often (see Appendix C, D, and E). Then, I narrowed down my terms even further to three words: “pale,” “fair,” and “white.” These all had the most data and appeared the most in each text. The primary focus of this study will be on a face flushing white or pale, rather than blushing red, especially because reddening complexions appeared less frequently.

Term: Pale

For a more accurate understanding of the complexion-related terms I have searched, the Oxford English Dictionary will provide the closest and most accurate definition of the word used during the Victorian period. Thus, there are two primary definitions of “pale” that are applicable during this time. “Pale” is defined as the following: “Of a person, a person’s complexion, etc.: of a whitish or ashen appearance; lacking healthy colour; pallid, wan, bloodless (typically connoting shock, strong emotion, or ill health)” (OED 1a) and “of colour; light, almost white; (of a specific colour) light in shade or hue” (1b). Searching this term in each text will reveal slightly different usages across the sentimental and sensational genres.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall used “pale” the least out of all the texts, only 30 times. Since it does not appear very often, the collocations are significant. Three instances related to the hue of an object, not the skin tone or color of a face. These examples only focused on describing the object. The other instances are related to the skin tone or change of a face. Observations of context surrounding this word reveal that “pale” is often associated with one specific character—Helen Graham.

The first time the word appears is when Gilbert lays eyes on Helen for the first time. He comments “her complexion was clear and pale” (Bronte, A 47) which indicates she is a naturally pale person. Other times Gilbert describes her complexion include the phrase “sweet, pale face” (56). However, the connotation of pale can change depending on the context. For example, later in the narrative as Helen struggles with her feelings for Gilbert and has to separate from him for a while, her face “was deadly pale” (340) due to the intensity of the conversation and her anxiety to part from him, thus making paleness a reaction to something bad.

Aside from Helen, the other times “pale” is used in this narrative is in relation to Frederick Lawrence, Helen’s brother. In the beginning, Gilbert does not know Frederick is Helen’s brother and assumes he is her lover. Out of jealousy, Gilbert attacks Frederick one day, leaving him with a head wound. After Gilbert reads Helen’s diary and finds out the truth of Fredericks’s identity, he goes to Lawrence’s house to apologize for the attack. Although Frederick is pale like his sister, during this incident, he was even more pale due to his injury. Gilbert points this out, saying “His usually pale face was flushed and feverish; his eyes were half closed, until he became sensible of my presence—and then he opened them wide enough” (344). Not only is Frederick pale due to the pain he is experiencing, he is also pale when Gilbert steps in: “And in truth the moisture started from his pores and stood on his pale forehead like dew” (344). Frederick is afraid of another attack while he suffers with his pain. Even though these are not explicitly stated as complexion changes, it reaffirms that paleness did come about through external stimuli such as sickness or from something sudden that causes the character to startle.

Unlike the other texts studied, Villette utilizes “pale” more as an adjective describing the color of an object than color of complexion. “Pale” appears 56 times throughout the story. According to Voyant Tools, the usage of “pale” started the middle of the narrative with the first appearance in Chapter VIII which was used to describe the hue of a crucifix hanging on a wall. When not describing the color of an inanimate object, “pale” precedes certain phrases that describe specific people in the novel.

Villette lacks in physiological or psychological complexion changes when using “pale.” That means the paleness of a character’s face is their skin tone. Pale skin is often regarded to be beautiful back in the Victorian period. This supports the dominant discourse of English people being the standard of beauty and overall superior over other ethnicities. Therefore, in this narrative, “pale” is used mostly to describe a character’s face or resting, normal skin tone.

For example, when Lucy learns of Paul Emmanuel’s past love Justine Marie, Lucy and other characters describe Justine as “pale.” Lucy relays the tale of Justine Marie’s past and describes the deceased nun as “pale Justine Marie” (Bronte, C 379) and later Madame Beck says “pale-faced Justine Marie” (383). Thus, in this instance, the context supports that Justine Marie is beautiful as other descriptions of her support her delicateness and holiness. Once again, her pale face is not the result of a disease or psychological reaction, rather it is her natural skin tone and a symbol of beauty.

The only instance of a change in complexion using “pale” happens to Lucy. Her changes happen primarily as a reaction to fear caused by external stimuli. Several times throughout the book, Lucy catches a glimpse of a ghostly figure, a nun, talked about in stories surrounding the foundation of Madame Beck’s school. The most terrifying appearance of the ghostly nun happened when Lucy was in the attic reading a letter from her godbrother Dr. John. The incidence startled her so much that she ran from the attic and fled to Madame Beck. Lucy’s sudden entrance to Madame Beck’s sitting room and their reactions to her appearance made her believe “My mortal fear and faintness must have made me deadly pale” (239) as they treated her gently and out of concern. The nun scared Lucy, resulting in her face turning pale and other physical reactions to her body.

The Woman in White uses “pale” 40 times. In this text, the word is used to describe the hue of objects such as hair and silk. However, this sensational novel embraces the word as more of a way to indicate complexion change, much more than the texts previously studied. This story mostly uses the phrase “turned pale” surrounded by negative context. Also, unlike the other texts, it does not use “pale” as a way to describe resting skin tone nearly as often as the sentimental stories did.

The first instance of a paling complexion change happens to Laura Fairlie, the young woman Walter Hartright is romantically interested in. Laura comes in after she had a serious conversation with her invalid uncle. Walter is unaware of what was exchanged between them. He observes her behavior at breakfast: “Her hand struck colder to mine than ever. She did not look at me, and she was very pale” (Collins 105). Laura’s reaction to the sudden news was an emotional response to the realization caused by hearing what her uncle said. Another change happens after her sister Marian brings up some logistics about the subject which is still unknown to Walter. Laura reacts even more frazzled than before: “Her fingers moved nervously among the crumbs that were scattered on the cloth. The paleness on her cheeks spread to her lips, and the lips themselves trembled visibly” (106). Thus, the internal realization, or whatever Laura now knows, is indirectly causing her to pale. There is no environmental factor, such as temperature or illness, creating the facial change.

It is important to note that most of the complexion changes happen to Laura Fairlie. Her complexion paled the first time because she realized she was going to be engaged to someone she barely knew, and she realized that she could not be with Walter. As the story progresses, Laura’s mood and behavior grows more upsetting. To help with her anxiety, Marian is allowed to stay with her at Percival’s estate. However, Marian finds Percival to be extremely suspicious after she is visited by his past wife Anne Catherick. Marian falls ill after hiding in the rain and listening to a conversation outside Percival’s window. She is taken from the estate by Count Fosco, Percival’s partner in crime.

Laura, still thinking Marian is there and sleeping away the illness, tries to visit her room but is stopped by Percival. He tells her she is no longer there, and she reacts: “Lady Glyde was not strong enough to bear the surprise of this extraordinary statement. She turned fearfully pale, and leaned back against the wall, looking at her husband in dead silence” (392). Once again, she pales out of fear and realization. She is afraid of Percival because of his temper and because of his power over her. She is also realizing that Marian, her only source of comfort in the house, is now gone.

Lady Audley’s Secret uses “pale” the most out of all the texts with 81 instances. The first usage is found within the first chapter of the narrative and follows a pattern throughout the rest of the story. “Pale” appears the most to describe antagonist Lucy Graham’s (aka. Helen Talboys and Helen Maldon) appearance. The term’s first usage happens when describing Lucy’s hair: “They were the most wonderful curls in the world—soft and feathery, always floating away from her face, and making a pale halo round her head when the sunlight shone through them” (Braddon 13). Here, pale describes the hue of her hair. It also has a positive connotation as its context of “making a pale halo” indicates Lucy’s flawless, angelic appearance. Her light complexion and light hair support the dominant discourse of whiteness being beautiful.

The first paling complexion change happens to Lucy in the first chapter as well. The rich Sir Michael Audley asked Lucy to be Lady Audley. She responds initially with a complexion change: “Lucy Graham dropped the brush upon the picture, and flushed scarlet to the roots of her fair hair; and then grew pale again, far paler than Mrs. Dawson had ever seen her before” (13). Initially, the blushing and paling are a result of indirect stimuli—Lucy being told to be his wife—and she is so surprised that she blushes and pales. However, a second reading of the book hints at Lucy’s inner intentions that her goal was to marry a rich man, and she succeeded in doing that. Although the true reason for her paling is not explicitly stated, it may be inferred that it isn’t just shock that she was proposed to, but also knowing that she is about to enter a new relationship under a fake identity which may lead her to feel some sort of guilt.

When Robert Audley starts his search for clues about George Talboys’s disappearance, he begins to suspect Lucy Audley to have something to do with it. He starts to trace back her life and starts to unravel the web of lies surrounding her identity. At one point, Robert visits the Audleys’ home. There, Lucy asks how his search is going and he reacts: “Something in the aspect of her bright young beauty, something in the childish innocence of her expression, seemed to smite him to the heart, and his face grew ghastly pale as he looked at her” (224). He grows pale not because of any environmental factors but because he is scared of Lucy and suspects she hurt George Talboys. This book more than the other selections use “pale” as more of a reaction to internal thoughts and emotions.

In the sentimental texts, “pale” is not used as a changing complexion color. Instead, it is used either as an adjective describing the hue of an object or as a resting complexion color. Characters such as Helen Graham and Justine Marie are associated with pale, and when it is used to describe them, it has more of a positive connotation because it refers to their fairness and beauty rather than a negative pale like if they were sick. On the other hand, the sensational texts do use “pale” as a change in complexion color. Variations of the phrases “turning pale” and “grew pale” were common in these texts to show internal realization as an external reaction.

Term: Fair

The next term “fair” was defined as “Beautiful to the eye; of attractive appearance; good-looking” (OED 1). According to the dictionary, this adjective was used mostly to describe the following: “of a person, or a person's face, figure,” (1a) “of an inanimate thing,” (1b) and “of appearance, colour, personal qualities, or attributes etc.” (1c). In sentimental and sensational fiction, this word was used quite often, but both genres had some subtle differences in how and where they used this term. It has a more positive connotation than “pale” does. For example, it may be used in a way to indicate someone’s innocence. Additionally, faces do not normally change to “fair,” but it is usually the resting state of a face’s complexion; a person’s fairness is natural and permanent.

“Fair” is used the most in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall with 39 times. Observations of where the words are used and how they are used shows that “fair” is used as an adjective to describe a character’s appearance. More specifically, “fair” is found the most in Gilbert Markham’s narrative and is mostly found describing his love interest, Helen Graham. As for Helen’s diary entries, she barely uses that word.

The first time “fair” appears in the novel is in the first chapter when Gilbert’s family learns of a widow moving into the long vacant Wildfell Hall, a large house a few miles away from their home. Gilbert writes about his family’s first encounter with the widow, Helen Graham, stating “The next day my mother and Rose hastened to pay their compliments to the fair recluse; and came back but little wiser than they went…” (Bronte, A 45). He follows this pattern many times throughout his narrative, addressing Helen as a fair character. He does not explicitly state that she looks fair, but rather he conveys this like it is a title for her. He refers to her as “fair unknown,” “fair antagonist,” and “fair artist” as he begins to form a friendship with her.

In this novel, “fair” is not used to indicate a change in complexion. Like Villette’s usage of “pale” as a resting skin tone for several characters, “fair” is used the same way in Tenant of Wildfell Hall. When Gilbert describes Helen’s skin or complexion, he calls it “fair.” For example, when he sees Helen outside with her son, Arthur, Gilbert comments: “How lovely she looked with her dark ringlets streaming in the light summer breeze, her fair cheek slightly flushed, and her countenance radiant with smiles!” (102). There is an instance of complexion change in this sentence, as her face flushed, but there is not enough context to support why her face flushed. The main point is that her skin is pale and fair when there is no change in complexion.

Next, Villette has the second highest frequency next to Tenant which is 38 times. In this book, “fair” is used as an adjective to describe a character’s appearance as pleasant. The other times the word appears is used as a descriptor meaning that something is okay. Next, “fair” is a more positive word than “pale.” “Pale” often accompanies sickness or fatigue, but “fair” is a positive word that is used more for skin tone. Again, Villette neglects using this term to show a complexion change due to physiological or psychological conditions.

One description containing “fair” was of a drawing. When Lucy runs into her godfamily again (although she does not know it at the time), she stays at their Villette home for the night. She observes the room and finds a drawing on the wall. She describes it as “a youth of sixteen, fair-complexioned, with sanguine health in his cheeks…” (Bronte, C 166). In this example, “fair” is positively connotated and does not represent a change in complexion, but how a complexion is normally.

The other most common instances of “fair” was associated with two characters: Ginevra Fanshawe and Paulina Home. The protagonist, Lucy, is a very observant person and is critical of appearance and behavior of people when she first meets them. When Lucy first met Ginevra, she noted how different they both are as people. Lucy, who is calm and introverted, made a general observation of Ginevra: “Many a time since have I noticed, in persons of Ginevra Fanshawe's light, careless temperament, and fair, fragile style of beauty, an entire incapacity to endure: they seem to sour in adversity, like small beer in thunder” (57). She is beautiful and fair, but her selfishness and other personality traits seem to dull her appearance over time. In addition, other mentions of Ginevra in the story regard her as “fair” or “fairest,” but they too did not regard a change in complexion. Paulina Home is also described as such in appearance and as a “fair little daughter” (277). Her fairness is not only in her beauty but in her childish innocence. The Woman in White uses “fair” 28 times. Just like the previous texts, “fair” is not used as a complexion change but rather to show the resting skin tone of a character. Most of the usages in this text involve fair as an adjective to describe something in a considerable amount or something as decent. The times when “fair” is used to describe skin tone or appearance happens primarily to Laura Fairlie. Once again, “fair” has a more positive connotation than “pale” because it mainly references beauty.

When Laura is first talked about by her sister Marian, Marian says “I am dark and ugly, and she is fair and pretty” (Collins 76). Laura is not only blonde but she is also extremely white which was a standard of beauty during this time. Marian’s hair was darker and she had tanner skin, hence why she is not described as “fair.” In addition, because Laura is already a fair person, the times when her complexion whitens are significant because there is a difference between fair skin and beauty, and such a white complexion indicates underlying emotional problems or is caused by the environment.

Lady Audley’s Secret uses “fair” 30 times. Once again, “fair” has a more positive connotation than “pale,” but this text uses “fair” differently than the other novels. “Fair,” like “pale” is mostly associated with Lucy Audley. However, since “fair” describes Lady Audley so often, it acts as a word that reinforces her beauty. Since beauty is often connected to innocence, observations of Lucy’s fairness may throw a reader’s opinion of her off track. One moment they may assume she is guilty because she pales so often, but with constant descriptions of being beautiful and fair may swing the opinion back in her favor—that she is innocent.

Before Robert Audley meets Lucy for the first time, he hears about how beautiful and wonderful she is from his family. He describes her twice as a “fair-haired paragon” (Braddon 48 and 52) which shows that he believes her to look and act flawless before he even meets her. However, after he meets her and after the disappearance of George Talboys, Robert’s descriptions change to reflect a more suspicious, negative tone. For example, after Robert gathered some information about Lucy’s past, he goes to Audley Court to confront Lucy about the circumstantial evidence he found:

Are women merciful, or loving, or kind in proportion to their beauty and grace? Was there not a certain Monsieur Mazers de Latude, who had the bad fortune to offend the all-accomplished Madam de Pompadour, who expiated his youthful indiscretion by a life-long imprisonment; who twice escaped from prison, to be twice cast back into captivity; who, trusting in the tardy generosity of his beautiful foe, betrayed himself to an implacable fiend? Robert Audley looked at the pale face of the woman standing by his side; that fair [my emphasis] and beautiful face, illumined by starry-blue eyes, that had a strange and surely a dangerous light in them; and remembering a hundred stories of womanly perfidy, shuddered as he thought how unequal the struggle might be between himself and his uncle's wife. (Braddon 234)

Now knowing some truth to Lucy’s past, Robert is scared for his uncle, scared for himself, and scared at the thought of what happened to George. The surrounding context, specifically asking if women are hellish creatures and what they are capable of, changes the underlying meaning of “fair.” He now points out her fairness to manipulate others and look innocent rather than being positively connected to simple beauty. Finally, there are no instances in this text that directly indicate a complexion change using “fair” and instead uses it as a resting skin tone or color.

Both sentimental and sensational texts use “fair” not as a word to describe a change in complexion but rather it describes the resting state of a complexion. In the sentimental texts and in one of the sensational texts, The Woman in White, use “fair” as a word that not only describes the skin tone of the character but also subliminally highlights how fairness during this period was viewed as the superior beauty standard. The one text that uses “fair” in a different way is Lady Audley’s Secret. In that book, “fair” not only describes Lucy Audley’s beauty, but also implies her innocence. Beauty is associated with innocence and goodness so the author constantly applying it to Lucy may create confusion because it is difficult to believe such a beautiful, fair woman could be associated with unspeakable crimes.

Term: White

The final term “white” is used as an adjective and was defined as “In senses referring to physical appearance or physical properties” (OED I). It is often used to describe colors of objects, but also it can describe complexion. A more specific use of it is defined as “Of or with reference to the skin or complexion: light in colour, pale, fair” (3) or “abnormally pale or pallid, esp. from illness, or from fear or other emotion” (4a). This word is different from the previous terms as it is the extreme version of “pale” and “fair.” Additionally, “white” is used primarily as a word indicating complexion, much more commonly than the other words studied.

Anne Bronte did not share Charlotte Bronte’s love for the word “white.” Very different from her sister’s book, Anne only used “white” 26 times in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, the least out of all the novels in this study. However, because it is used less often as the other novels, the collocations accompanying “white” are much more significant. Again, this word describes a complexion change, but in this novel, it is not bound to specific characters as it could be in other novels.

Like other texts, “white” appears a few times to simply describe the resting skin tone of the character. Gilbert often observes Helen’s features and, on more than one occasion, points out the whiteness of her hands. When he watches her draw, he describes “the elegant white hands that held the pencil” (Bronte, A 85). When Helen is away to tend to her dying husband, Gilbert remains in the know about her whereabouts from her brother, Frederick Lawrence. They become good friends and at one point, Gilbert takes Frederick’s hands, going as far to describe them in relation to Helen. He says: “I took a secret delight in pressing those slender white fingers, so marvelously like her own” (347-48). The whiteness of skin tone is associated with Helen’s fair beauty.

As previously stated, “white” is used regarding complexion changes in this novel whereas “pale” and “fair” were not. The action of “turning white” is scattered several times throughout the narrative. The first instance of which happens to Frederick Lawrence. At a dinner party, Gilbert attempts to take Frederick into conversation to find out more about Helen, when Frederick comments that Gilbert should have no hope to enter a relationship with her. Gilbert, assuming Frederick liked her too, called him a hypocrite. In response, Frederick “held his breath, and looked very blank, turned white about the gills, and went away without another word” (100). The sudden outburst from Gilbert shocked Frederick, causing him to pale. In other words, the outer stimulus of a sudden yell frightened Frederick which resulted in his white complexion.

Gilbert had another fiery exchange with Frederick a few chapters later. One night, Gilbert saw Frederick with Helen at Wildfell Hall, and he overheard a portion of their private conversation. How they talked and how they acted led Gilbert to feel even more suspicious over Frederick’s seemingly overprotective relationship with Helen. A few days later, Gilbert rides down the road and finds Frederick riding back from the hall. After a passive aggressive spat, Gilbert impulsively smacks Frederick in the head with the end of his riding whip. Frederick falls off his horse, and Gilbert rides away. A short time later, Gilbert comes upon Frederick again, still laying in the road:

I found him seated in a recumbent position on the bank,—looking very white [my emphasis] and sickly still, and holding his cambric handkerchief (now more red than white) to his head. It must have been a powerful blow; but half the credit—or the blame of it (which you please) must be attributed to the whip, which was garnished with a massive horse’s head of plated metal. (121)

Here, Frederick’s whiteness is a result of his injury. The harsh impact of the riding whip on his skull followed by the loss of blood from the gash in his head causes his complexion to turn sickly white. This is an example of an outside force causing a negative change in complexion color.

Villette has the highest frequency of “white” compared to the other sentimental novel with 119 times. Just like the previous terms this story utilizes, “white” is not used as much to indicate a shift in complexion but rather the normal state of complexion or a descriptor of the color of an object or aspect of a person. In fact, the first usage of “white” in the context of a complexion change is not mentioned until Chapter 14 (see Appendix C) when Lucy is scolding Ginevra Fanshawe on leading so many men on with her “pink and white complexion” (Bronte, C 145). This is another instance of complexion by itself and not caused by any external or internal stimuli. Ginevra is simply a fair person and that vocabulary backs up her beauty.

A clear instance of color change in a character’s face was indicated in dialogue exchanged between Lucy and Dr. John. They are conversing about their correspondence through letters when Lucy remembers the paranormal experience she encountered in the attic of the school. Dr. John says “”You looked white as the wall; but you only spoke of 'something,' not defining what. Was it a man? Was it an animal? What was it?”” (241). The external stimuli of seeing the ghostly nun in the attic caused Lucy to turn white with fear. Another instance of white complexion is caused by illness and dread which is a result of Lucy finding out that she cannot marry M. Paul from Madame Beck: “for Ginevra, like the rest, thought I had a headache—an intolerable headache which made me frightfully white in the face, and insanely restless in the foot” (432). A significant finding is that the only complexion changes in this novel including the word “white” happen to Lucy.

The Woman in White uses “white” the most with 147 instances. Like in the sentimental texts, “white” can be an adjective to describe the lack of color in an object. The titular phrase “woman in white” is the most common phrase containing “white” in the book, but it simply referred to a woman in a white dress, not anything related to the face. The first appearance of the word as a complexion change happens in Chapter IX when Marian tells Walter that Laura is engaged: “Her large black eyes were rooted on me, watching the white change on my face, which I felt, and which she saw” (Collins 110). The heartbreak and shock caused the change in his face. He even felt the blood leave his face and he knows that Marian sees that. He tries to act composed, but his face reveals the inner turmoil he struggles with.

Marian feels guilty for telling Walter and for turning him away from their house. She reflects on this in her diary when Laura tells her of Percival’s anger. Marian remembers “The white despair of Walter's face, when my cruel words struck him to the heart in the summer-house at Limmeridge, rose before me in mute, unendurable reproach” (282). “White” describes the despair on Walter’s face. It implies the shock and sorrow that shocked him into becoming pale.

Another major complexion change happened in Mrs. Catherick’s narrative. She is the mother of the “woman in white,” Anne Catherick. She also knew Percival’s secrets and his true identity—he was not a baronet and had no noblemen in his family line to make him one. He told Mrs. Catherick not to tell anyone, but Anne blurted out that she knew his secret. In response, Percival “sat speechless, as white as the paper I am writing on, while I pushed her out of the room” (533). Percival turns white out of shock and fear because he told Mrs. Catherick not to tell anyone or there would be consequences. At the same time, he realizes what a danger Anne is to his reputation.

Lady Audley’s Secret uses “white” 73 times. Unlike the other texts, this novel does not use “white” to describe an objects hue nearly as often. Instead, it uses that term more to indicate a change in complexion color or as a resting skin tone. In addition, there are some cases where “white” is used as a general descriptor of a person’s current state. Phrases like “seated herself on the edge of the white bed, still and white as the draperies hanging around her” (Braddon 16) and “he sat rigid, white and helpless” (37) are examples of white as a general descriptor. Their figures appear white whether that be the lighting they are in or the color of their clothes.

The first major complexion change using “white” happens when George Talboys arrives in England after a long boat ride from Australia. He is expecting a letter to be waiting for him once he is there. That letter is a reply from his wife, Helen Talboys, and a response to his previous correspondence stating he was on his way home. As he waits for someone to look and see if he has any mail, George happens to look at a newspaper to pass the time. However, he reacts unexpectedly: “…after considerable pause he pushed the newspaper over to Robert Audley, and with a face that had changed from its dark bronze to a sickly, chalky grayish white…” (36). He turns white because he realizes that his wife died before he could make it back to England and her obituary is in the paper.

After George disappears and Robert finds some clues tying Lucy Audley to the disappearance of his friend, Robert heads back to Audley court to confront her. She asks him where he had been lately, and he replies that he was in Yorkshire, a town that she was connected with in her past. Her response is unfavorable: “The white change in my lady's face was the only sign of her having heard these words. She smiled, a faint, sickly smile, and tried to pass her husband's nephew” (224). Robert studies her paling response which implies he is studying her inner character. To an outsider, there is no reason as to why her face pales in response to his whereabouts, but because he knows some of her past now, he may infer that she is guilty about something. She also knows that he is suspicious with her due to how he is actively searching for clues about her past.

Another instance of paling happens when Alicia Audley (Sir Michael Audley’s daughter and subsequently Robert Audley’s cousin) talks about Robert staying at Mount Stanning, a nearby inn. Unbeknownst to Alicia, however, Lucy Audley traveled there the night before to burn it down because she knew Robert was inside. The narrator asks the reader a hypothetical question and then describes Lucy Audley’s reaction:

Have you ever heard anybody, whom you knew to be dead, alluded to in a light, easy going manner by another person who did not know of his death—alluded to as doing that or this, as performing some trivial everyday operation—when you know that he has vanished away from the face of this earth, and separated himself forever from all living creatures and their commonplace pursuits in the awful solemnity of death? Such a chance allusion, insignificant though it may be, is apt to send a strange thrill of pain through the mind. The ignorant remark jars discordantly upon the hyper-sensitive brain; the King of Terrors is desecrated by that unwitting disrespect. Heaven knows what hidden reason my lady may have had for experiencing some such revulsion of feeling on the sudden mention of Mr. Audley's name, but her pale face blanched to a sickly white [my emphasis] as Alicia Audley spoke of her cousin (279)

Lucy’s blanched expression goes unnoticed by her husband and Alicia. Alicia babbles on about Robert some more, not thinking anything of Lucy and her manner. Lucy’s complexion change is a key instance of guilt, and the knowing of information that others do not know at the time, as a catalyst of whitening complexion. This shows her internal character, specifically how scared she is of people finding out that she burned the inn down and of finding out her true identity. The addition of complexion changes in this novel subtly point at the true nature of characters such as Lucy’s fear of being caught and how she is hiding things that people do not know which triggers whitening in the face. Additionally, the paragraph surrounding the term emphasizes the uneasiness that accompanies the mentioning of a person that experienced extreme trauma, especially when not everyone knows it. This context is important because it impacts how Lucy Audley’s whitening complexion is interpreted. Since she is the only one that knows, she is guilty of something.

Once again, the sentimental texts used “white” more as an adjective to describe the color of objects or resting skin tones rather than complexion changes. When complexion changes did take place, they were most commonly in response to external stimuli such as fear (like when Lucy Snowe encountered the ghostly nun in Villette) and sickness or injury (when Frederick Lawrence was wounded and lost a fair amount of blood in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall). The sensational texts had the opposite results. Whitening faces occurred when intense realization happened within a character. For example, Walter Hartright turned white when he found out about Laura Fairlie’s engagement in The Woman in White and Lucy Audley turned white when her family spoke of Robert Audley who she presumably killed in a hotel fire in Lady Audley’s Secret.

Findings and Interpretations

Although this research is subjective, the findings shed light on how both genres of fiction utilized complexion related terms. Even though the definitions of the words did not change in the texts, the context surrounding them had the ability to impact how they could be interpreted. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall centralized its complexion changes and complexion descriptions on Helen Graham. Not only was she the female protagonist and love interest to Gilbert, but she also went through many situations that resulted in complexion changes or intense descriptions of appearance. Gilbert’s infatuation with Helen was evident in how he described her, especially as he referred to her pale skin so often. Additionally, Helen’s changes in her face were usually in response with what Gilbert said or did with her. Although she is a proper, quiet woman, she acts particularly anxious around Gilbert in the beginning and later after he reads her diary. Her paling happened when she was nervous, and she was pale in general. The other character that had significant complexion changes was her brother Frederick Lawrence. After Gilbert’s attack on him, Frederick was pale due to blood loss and pain. When he saw Gilbert again a few days after the attack, he turned pale out of fear that Gilbert would hurt him again. Overall, most complexion changes in this novel were caused by external conditions. Internal character was not a priority as the domestic sphere and public sphere were emphasized to remain separate entities.

Villette had the strangest instances of the terms. Rather than complexion changing, the terms were used more as adjectives to describe an object or the normal appearance of a character. When the terms were used to describe a complexion change, they resulted from physiological changes caused by external stimuli. A person was either very white due to an illness or that was their natural skin tone. For example, Ginevra and Polly were both described as “fair” characters due to their soft appearances. Then, the most complexion changes happened to Lucy, but they were the result of fatigue, worry, and the few instances she was scared by the apparition of a nun. Villette seemed more concerned with general appearances, such as if someone was dressed up during a certain scene. Internal character and motives were not a priority.

Throughout the sentimental texts, I noticed a distinct pattern. Starting with The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, the complexion-change words of “fair,” “pale,” and “white” were mostly used to describe the color of an object or skin tone. There are only a handful of instances that use these words to describe a complexion change and when a change did happen, they were either due to shock or sickness. Next, Villette had the same pattern. However, Villette had less instances of these terms used as a complexion change, specifically changes caused by external stimuli. As for internal stimuli causing change, there were barely any usages of this in either sentimental novel. This shows that as time progressed closer toward the appearance of sensational fiction, the usage of complexion-change terms caused by external stimuli was not used as often. In other words, facial color changes caused by fear, shock, illness, and other external factors became less common as sensational fiction came into play. That meant that facial color changes caused by internal stimuli started to rise once sensational fiction grew popular.

The Woman in White, the first sensational novel out of the selections, started to show the shift of complexion related vocabulary. Because this novel deals with crime and mystery, the complexion changes used here were used more to show internal realization which usually was surrounded by negative context. For instance, when Sir Percival found out that more people knew his secret than he realized, he turned white because of that realization and then had to formulate how to take care of that problem. When Walter Hartright found out that Laura was engaged, he turned white because he realized he could not be with her. Of course, there remains instances of static complexions or resting skin tones in this text like the other novels studied. However, Collins’s tendency to use complexion changes as a way to subliminally show a character’s inner feelings—such as Percival’s fear for being found out and anger at those who knows his secret—helped shape the genre of sensational fiction and established a more psychological emphasis on any shifts in the face, whether that be color or expression.

Lady Audley’s Secret has the most radical shift in complexion vocabulary. It takes what The Woman in White established with more psychological, internal reactions that result in a change in facial color. Again, Lady Audley’s Secret does use complexion changes in response to external forces like every text studied. Every text includes such changes which suggests that complexion changes were still important even in situations that did not use them to study a character’s internal motives. Instead, those outside reactions to sickness, fatigue, worry, or fear add depth to the narrative and provide a way to show, not just tell, a reaction to specific stimuli. Like the other sensational text, this story also utilizes a lot of complexion change to show internal motives or guilt. This text out of all of them uses that idea the most, especially with Lady Audley. She is described as “fair” because that is a beauty standard and makes her look like a beautiful, trustworthy woman, but her paling responses to Robert Audley’s suspicion of her implies that her beauty is a disguise. She pales because she does not want to get caught and she is guilty of what Robert suspects she has done.

In the sensational texts, I noticed a pattern that was close to the pattern I found in sentimental texts. It also includes “fair,” “pale,” and “white” as general words to describe objects colors or resting skin tones. It did not use external stimuli to cause complexion changes as often as sentimental. There were a few instances of this in The Woman in White but even less in Lady Audley’s Secret. Thus, where sentimental texts used this more often and it started out as the dominant way to describe complexion changes, it decreased over time. Then, where sentimental texts did not use internally caused complexion changes, it increases over time. It starts out in The Woman in White and is used as the primary way to show complexion changes in Lady Audley’s Secret.

Conclusion

The data and findings gathered display an interesting change of how complexion changes were used across sentimental and sensational fiction. While whitening complexions caused by external factors in sentimental fiction started out strong, and used more often, that usage of complexion change slowly decreased over time and was not as prevalent in sensational fiction. On the other hand, complexion changes from internal stimuli, or realization, started out slowly and appeared less commonly in sentimental fiction, but it became more popular in sensational texts. In other words, complexion changes caused by external factors decreased over time from sentimental fiction to sensational fiction whereas complexion changes caused by internal factors increased over time from sentimental fiction to sensational fiction.

In The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, whitening faces leaned mostly toward a response to sickness and fear caused by external sources. Villette also embraced those ideas but used them more sparingly. In fact, it didn’t focus on many changes in the face at all and rather their resting appearances. The only notable complexion changes happen from external stimuli triggering fear. Additionally, it was used in a creative way since the cause of fear (the ghost of the nun) is more of a supernatural element and is expected to appear more in a sensational novel due to its derivation from realism.

The transition from sentimental into sensational showed a shift in how facial changes were viewed in narratives. Once again, sentimental focused more on the external forces that caused change in the face such as sickness or a scare, but sensational took it a step farther and included internal forces that caused complexion changes such as realization, guilt, or other negative emotions or thoughts. The Woman in White was the first novel to set a standard for sensational fiction. It stepped away from the normal reasons for paling complexions commonly found in sentimental fiction. It competed with the dominant discourse and interfered with the domestic sphere. It peered into how characters truly felt. Lady Audley’s Secret did this as well but had even more instances of complexion change to subliminally hint at a character’s guilt for a crime they committed.

This study emphasizes the importance of how societal views at the time may shift the meanings of certain words in narratives or other media. The traditional definitions of words stuck, but the surrounding context in the narratives hint at subliminal, subconscious reasons as to why the complexion change took place. At one point when sentimental texts were more common, complexion changes happened due to an external force and resulted from coldness, sickness, or fatigue. There was no underlying emotional reason as to why the complexion changed the way it did. Although sentimental fiction pushed for highly emotional responses, emotions were not as closely connected to facial changes as they were later on in sensational texts.

Despite only using four texts for this research, this project can easily expand to encompass more narratives. It is also capable of focusing on different types of vocabulary. The same research may be performed on more sentimental and sensational texts which would provide a broader pool of data. More texts may provide further support that dominant discourses and context shaped meanings of complexion related vocabulary. Regarding the topic of complexion changes, another, separate analysis of reddening complexions may be studied and compared to the results of this analysis.

Even though the study can be expanded, there are some limitations for this type of research. First, the conclusions and ideas behind how terms are used are subjective. One reader may interpret the shift in meaning to be caused by one thing whereas another reader may think the meaning was caused by another. The one aspect of this study that is not subjective is the research of the frequency of terms and exclusions of other terms which be proven through digital tools that count such words. Another limitation is that this kind of rhetorical study may not apply to all genres. The choice of sentimental to sensational fiction over the period of a few decades shows how quickly the context of complexion changes shifted. Some other genres or literary periods may not have an easily identifiable vocabulary change or insufficient evidence to prove a thesis true.

Appendix

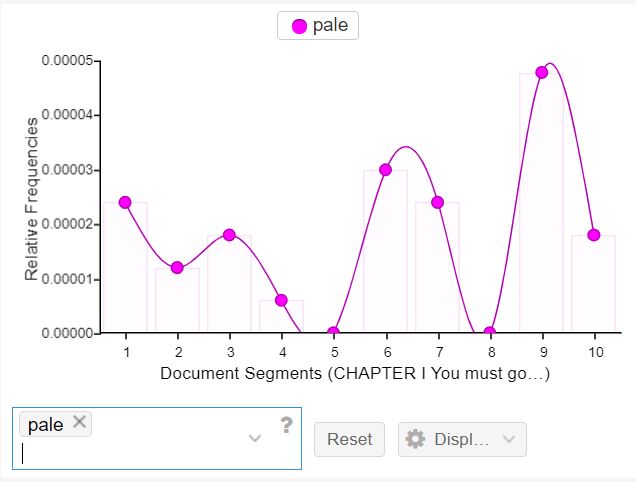

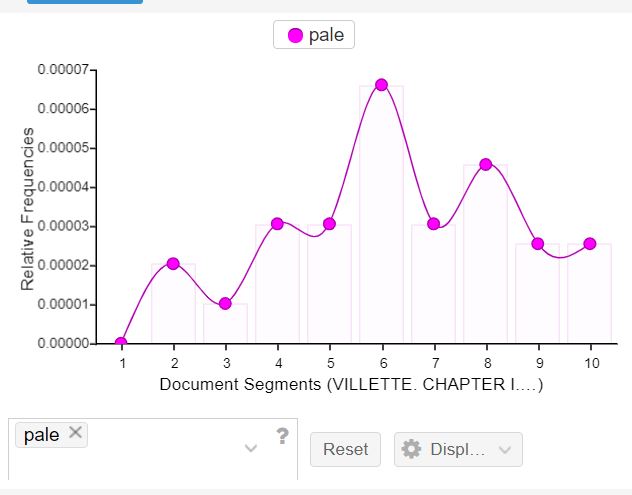

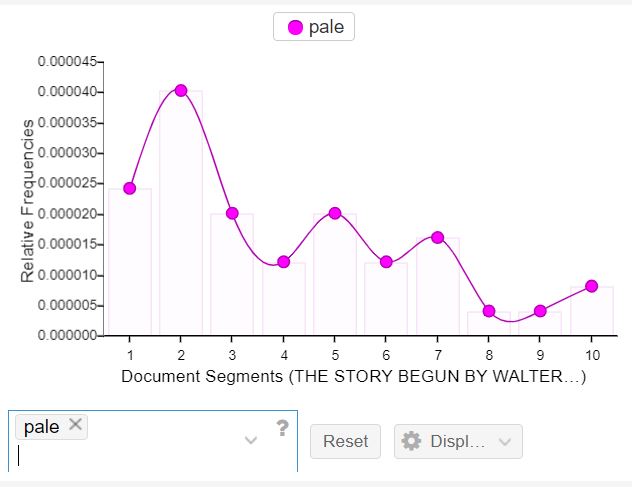

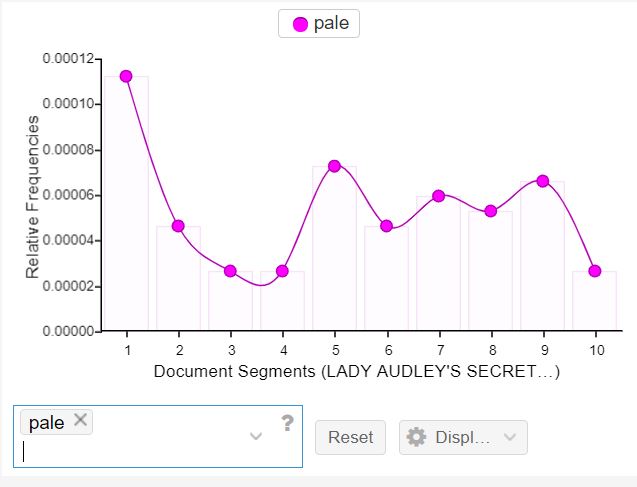

1. Visuals of frequency and usage of “pale” throughout all novels (color of graph and numbers are insignificant)

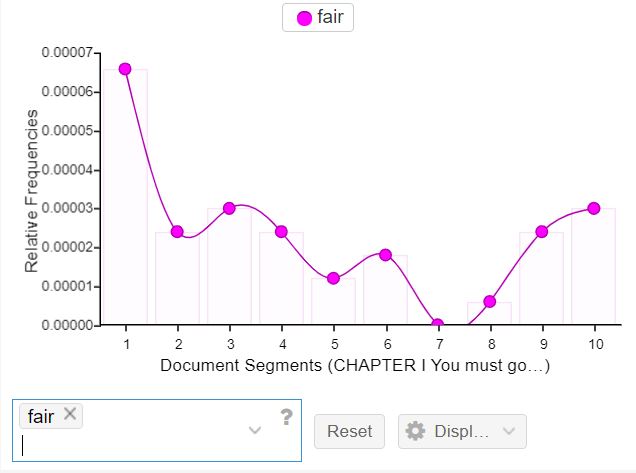

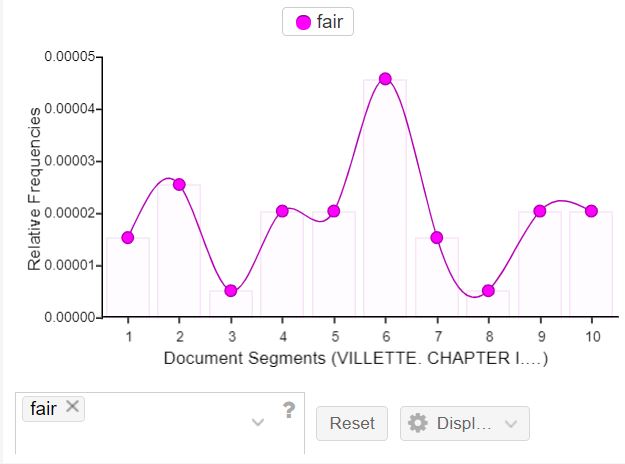

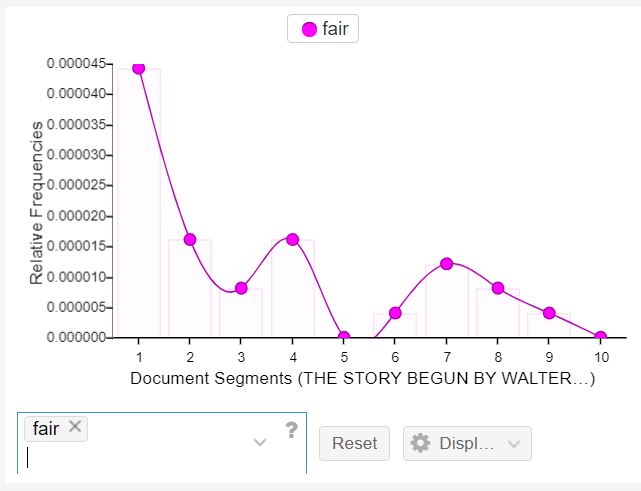

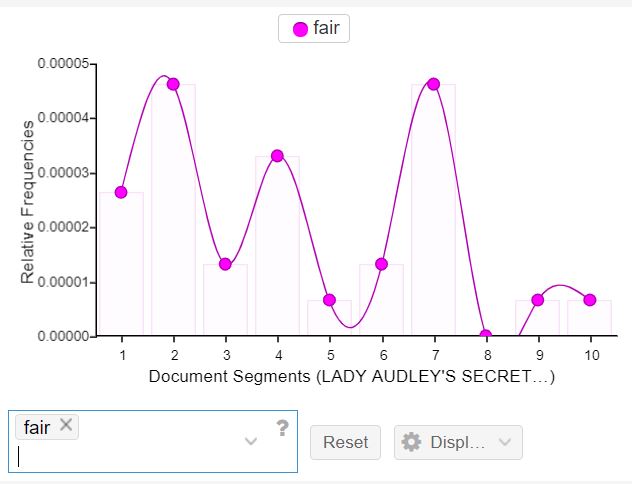

2. Visuals of frequency and usage of “fair” throughout all novels (color of graph and numbers are insignificant)

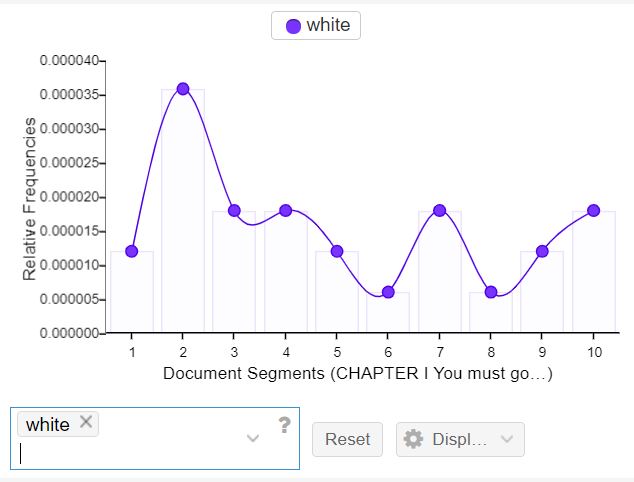

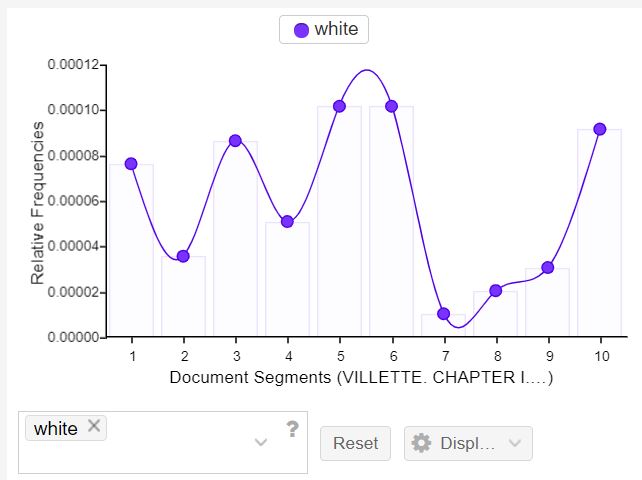

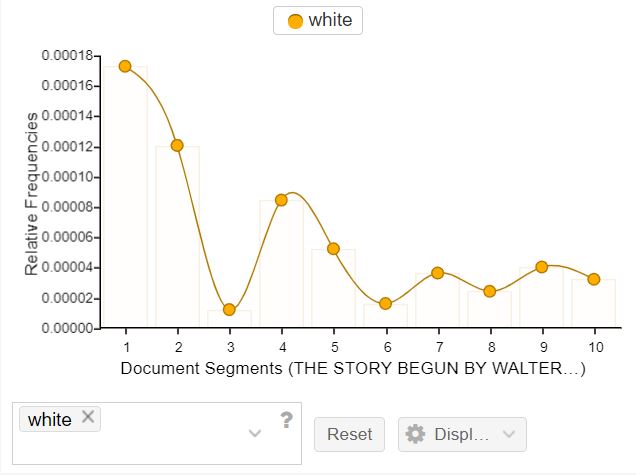

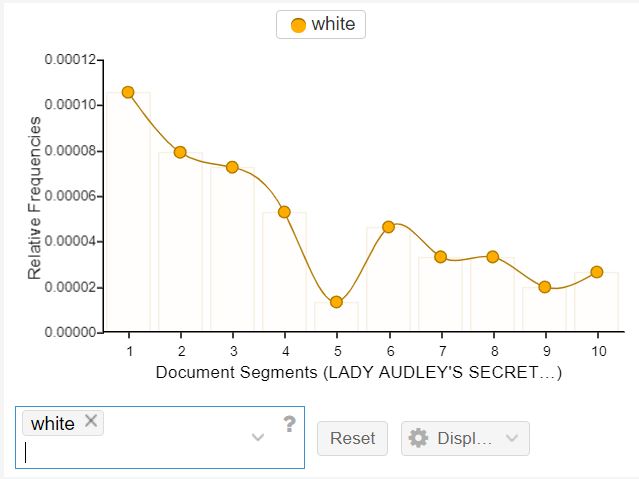

3. Visuals of frequency and usage of “white” throughout all novels (color of graph and numbers are insignificant)

Works Cited

Braddon, Mary Elizabeth. Lady Audley’s Secret. Edited by Lyn Pykett, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Bronte, Anne. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Edited by Lee A. Talley, Broadview, 2009.

Bronte, Charlotte. Villette. Arcturus, 2011.

Collins, Wilkie. The Woman in White. Edited by Maria K Bachman and Don Richard Cox, Broadview Press, 2006.

O’Farrell, Mary Ann. Telling Complexions: The Nineteenth-Century English Novel and the Blush. Duke University Press, 1997.

Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2020.

Unknown. “Oxford Reference: Sensibility.” Oxford Reference, Oxford University Press, 2020.

Poovey, Mary. Making a Social Body. The University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Poovey, Mary. The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer. The University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Pykett, Lyn. The Sensation Novel from The Woman in White to The Moonstone. Northcote House, 1994.